ARTISTIC METHODS

The relationship between an artwork and a site can exist in a so-called site-referenced work: an artist’s specific response to a location, place and/or community. ReSpace commissioned artists, Susan Sloan (UK), Dritero Nikqi (Kosovo) and Alfred Muchilwa (Kenya/Rwanda) to look at their responses to the different sites as experienced in-situ, remotely and through collaborations with young people from Kosovo, Rwanda and the UK. This collaboration was both about creating a series of artworks as well as exploring a range of artistic practices. In fact artistic practice is understood as a mode of inquiry that connects to the site leading to a better understanding of a place.

In this project, we are interested in examining how different artistic practices tie to the tangible and intangible qualities of space and place, their histories and past, present and future narratives. These different practices are intended to generate new knowledge and understanding about the site from the perspective of the young person. Through making sketches, taking photographs, recording soundscapes, using stop-motion, and creating 3D [VR] drawings and 3D CGI worlds, we invite young people to engage with the past, experience the present and imagine the future of the place of significance. Their use of these methods bring to the fore their subjective realities.

“It can also be argued that the process of making art and interpreting art adds to our understanding as new ideas are presented that help us see in new ways. These creative insights have the potential to transform our understanding by expanding the various descriptive, explanatory, and immersive systems of knowledge that frame individual and community awareness.” (Sullivan, 2010:97)

Animation

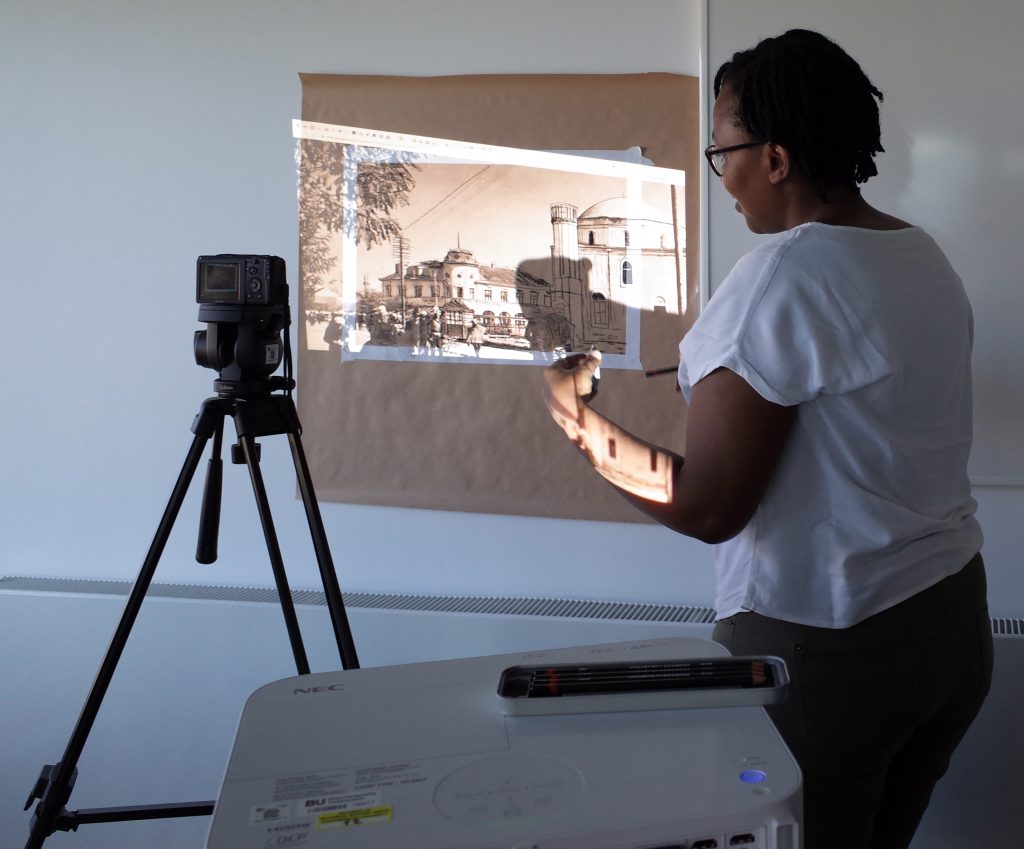

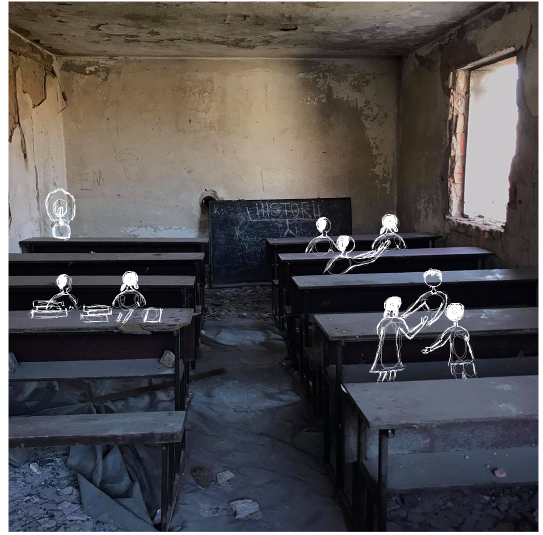

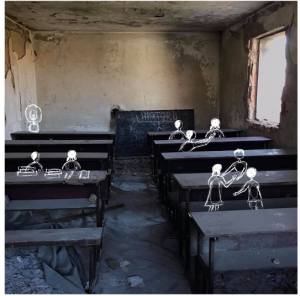

Animation exists as a practice that draws from a range of different artistic methods – whether using photography, drawing, illustration, sculpture – it is able to combine these with a temporal component. Change of state through time is intimately connected to the practice of animation, and thematically connected to this project as we consider sites that exist in different states through time.

In Kosovo, a house, then a school, then a museum – In Rwanda, an orphanage, then a school, then a cultural space. Using two under-the-camera techniques we invited young people to explore this change through time as a charcoal animation of an old postcard of a place, or as a stop-motion using materials that once made up a building and now exist as a pile of rubble.

Sound

The found sound and recording methodology explored the ways in which sound shapes and is shaped by our understandings of mnemonic and our acoustic environments. Sound has strong affinities with the most abstract social realities, it has historical and political dimensions.

IMAGE MAkING

Image Making is a key method of artistic investigation, and encompasses a variety of practices including drawing, sketching, filming, photography or a combination of these methods. The process of creation is informed and guided by critical reflection of the role of the researcher and artist and their own individual role within the wider discourse.

Anthropological Methods

Social or cultural anthropology engages with an array of ethnographic methods, which allow for the immersion of the researcher into a selected group’s shared ‘webs of significance’ (Geertz 1973) in a particular time/space context. In the case of ReSpace these webs were sought and found in particular places of historical, sociocultural, and political significance. We begin with the recognition that ethnography is both a way of knowing and a way of representing people and their practices. Without a methodological preoccupation with relativism, we not only nurture empathy and critical thinking, but also invite curiosity and confrontation with and about uncomfortable and conflicting histories.

The exercises we designed are meant to identify the shifting significance of places and events in order to explore and excavate personal, archival, official and silenced sites, as well as spaces in constant flux (political, social, cultural). As such they are made into sites grounding critical reflection.

One useful strategy of learning about Self and Other, which combines affective, causal and factual approaches, is the so-called Familiarisation/De-familiarisation strategy. With a long epistemological history rooted in the arts (Myers 2011), on the one hand, this method aims at uncovering what otherwise might remain implicit or taken-for-granted through ‘defamiliarisation’ techniques. On the other, through ‘familiarisation’, it fosters the ‘de-exotisising’ of perceived difference to people other than oneself across time or space, through immersion into their world, be this across generations and into the past; or across different groups or places anywhere, whether in the immediate vicinity near at home, or globally.

Combined with the visceral engagement of sensual ethnography with seemingly ordinary objects or spaces, the defamiliarisation technique can trigger critical insights and discussions about hidden or forgotten pasts and facilitate challenging the ‘politics of impossibility’ when imagining new futures. (Kazubowski-Houston 2020)

Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Kazubowski-Houston (2020). ‘Pedagogies of the Imagination: Toward a New Performative Politics’. In: P. R. Frese and S. Bownwell, eds, Experiential and Performative Anthropology in the Classroom: Engaging the Legacy of Edith and Victor Turner, 135 – 168. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Myers, R. (2011). ‘The Familiar Strange and the Strange Familiar in Anthropology and Beyond’, General Anthropology 18 (2): 1, 7-9.

Soja, Edward W. (1996). Thirdspace. Malden (Mass.): Blackwell, p. 57.

Sensory ethnography

Sensory ethnography, in particular, draws on phenomenological approaches to space and place through sensual experiences and affective learning about the past and the future. Sensory ethnography was proposed as a part of PAR – Participatory action research. It gives the practitioneres the tools to become critical interpretive researchers of their own lived experience, an action/participatory research framework that identifies critical thinking as the purpose of research and improved digital or data literacy as the outcome of research.

Interviews

In Dialogues with Anthropologists (2015), Prof. Judith Okely said “it is the free-ranging narratives of interviews, moving into dialogues, which bring new knowledge, precisely because unpredicted”.

There exist many types of interviews in qualitative research. They differ in the degree to which they are open, structured or guided by pre-determined themes and aims; how many people they involve on the side, and what research objectives the data harvested are supposed to serve.

Archival research

Archives are largely viewed as the basis of institucional memory, permanent data collection and storage. Archival research here is not the typical storage and collation . It is also rather traveling and connecting the past and the present. Considering the refraction, It leans to Thomas’s work of bearing witness refashions the ends of anthropology from the construction of inert archives of human difference to affective archives of violence..

Video Diary

Participatory visual methods can allow for researchers and participants to respond and produce self reflective ethnographic work. They can provide means for direct and individual feedback to the research process, as well as collective co-creation across spatial distances, as was the case with ReSpace, or any other collaborative platform that speaks to how resources, mobility and access are unequally structured.

Architectural Methods

Every architectural project is based on a specific site (or design problem) for which research and intervention are pursued in parallel. In pursuing any given architectural project we are reminded that architecture is primarily about design thinking expressed through drawing as a way of manifesting built form. Ideas, the basis of architectural exploration, are developed further through feedback and an iterative process. More and more, this iterative process is benefiting from investing in various media and techniques. For example, the use of mapping techniques photography, videography, simulation and narration. Whereas in their own right these are technical in nature, at the heart of it all is to make the process of architecture deeper and more meaningful in how it is conceived and later realised.

For that matter, as part of the ReSpace project, a nurturing approach was adopted as it creates a setting that encourages reflective practice, and supports a student’s individual development. Increasingly, a need to nurture future professionals is emerging, addressing what Weisman regards as a fundamental question for architectural education, which is ‘… not (about) how better to train future architects to compete against one another … but, rather how to improve the quality of architectural education and practice as inherently interrelated, life-affirming models for understanding the world at large, and each person’s belongingness to it’. This view embraces the idea of social justice, which we believe should be a core concern for architectural education, and influence the way we educate and nurture future architects.

Therefore, in collaboration with anthropology (UP), art (ADMA) and animation (BU) students and respective faculty, students of architecture and faculty of the University of Rwanda were immersed in an interdisciplinary exploration of the past, present and future of three sites (and people) through a series of mapping, drawing, reading, writing, reflective, audio and visual activities. These sites were selected for their history and current efforts to either enhance them (a memorial), relocate them (a school) or replan (an informal settlement). The outcome was more meaningful and alternative ways of viewing, knowing and disseminating the story of a place and its people.

Nóirín Hayes, ‘Teaching Matters in Early Educational Practice: The Case for a Nurturing Pedagogy’, Early Education and Development, 19.3 (2008), pp. 430-40.

Leslie Kanes Weisman, ‘Diversity by Design: Feminist Reflections on the Future of Architectural Education and Practice’, in The Sex of Architecture, ed. by Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), pp. 273-86 (p. 273)

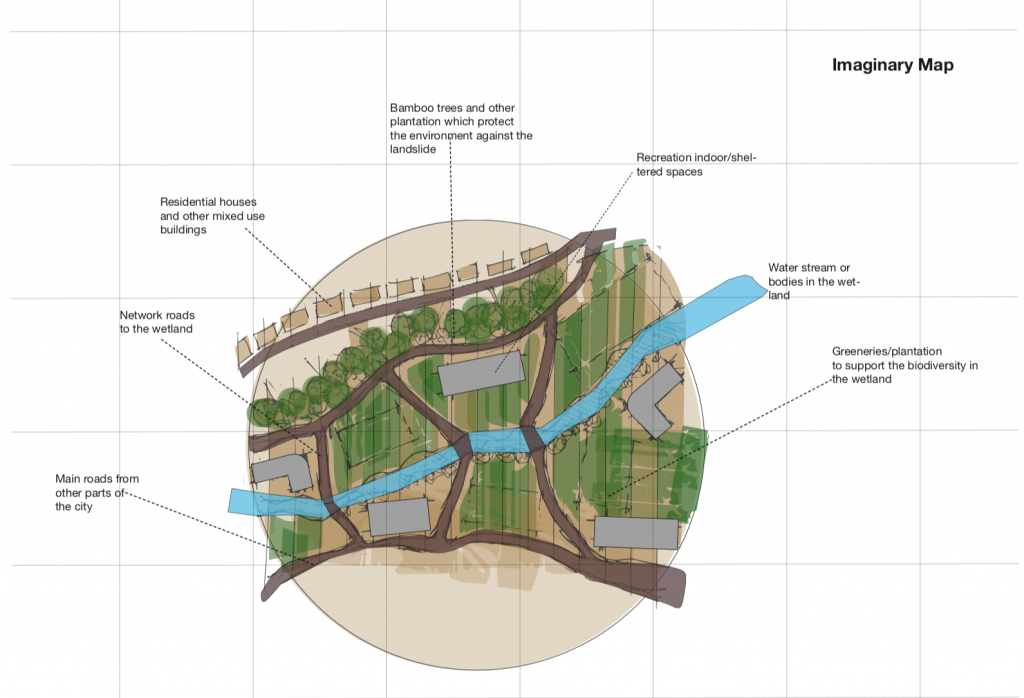

Mapping

As part of the ReSpace project, participants conducted sites visits during which they performed mapping as one of the methods of understanding the different sites that were visited.

Some of the mind maps were produced using sketches where students drew elements that are unique to each site. These maps are used to remember things visually, how they looked and their particularity. Other mind maps were produced using words..

Investigative Processes

Every architectural project is based on a specific site (or design problem) for which research and intervention are pursued in parallel. In pursuing any given architectural project we are reminded that architecture is primarily about design thinking expressed through drawing as a way of manifesting built form. Ideas, the basis of architectural exploration, are developed further through feedback and an iterative process. More and more, this iterative process is benefiting from investing in various media and techniques.

Walking

Before every site visit, participants undertook a walk that started from a point far from the sites. While during the systematic walking, participants were observing the different elements around the site, asking questions about different assets met along the way, listening to different stories about the sites, the different sounds and different smells around the site. Participants were also engaged in discussions about the different elements that they were meeting along the way, identifying some familiarities and similarities between the sites.

Surveys

Students captured photographs, 360 degree video and audio in and effort to document the sites in the present. These materials were set up in folders based on where the images, video and audio was recorded from and numbered. A google map of each site was then numbered corresponding to each locale.

Transdisciplinary Methods

The ReSpace project has from its inception been concerned with place, location, site, and space and movement to and from places both at a local and transnational level and responding to these spatial restrictions has been the team’s greatest challenge. The project was originally conceived of as shared experiences of various sites of significance in both Rwanda and Kosovo through which we would collectively investigate shared and contested memories and histories. The project set out to investigate how concepts of space could frame arts-based participatory methods to encourage the youth of a post-memory (Hirsch, 2008) generation in Rwanda and Kosovo to reimagine specific sites of memory and the dominant narratives that emerge from them. These participatory methods were phenomenologically connected to responses to space/place and designed to be contemporaneously explored by participants from Rwanda and Kosovo together. Therefore the restrictions in travel and movement across spaces during the COVID pandemic presented the project with a unique challenge: How could we understand a place from a distance? How could we experience a site whilst being geographically distant? How can we share that experience with peers in different locations? Was it possible to use available digital technologies to facilitate telepresence – ie. the feeling of being there?

Sketches

Drawing is a process that can be thought of as a mode of inquiry. It can be a way of thinking, of conveying information, a way of seeing, conceptualising, documenting and imagining. The process and time taken to draw requires the participant to be fully engaged and absorbed in the activity and their surroundings, seeing the familiar in a new way.

FilmING EACH OTHER

Whether through video diaries, video documentation or interviews, filming each other during the research captures research activities and provides documentation of the process, testimonials of these experiences and resources for future research

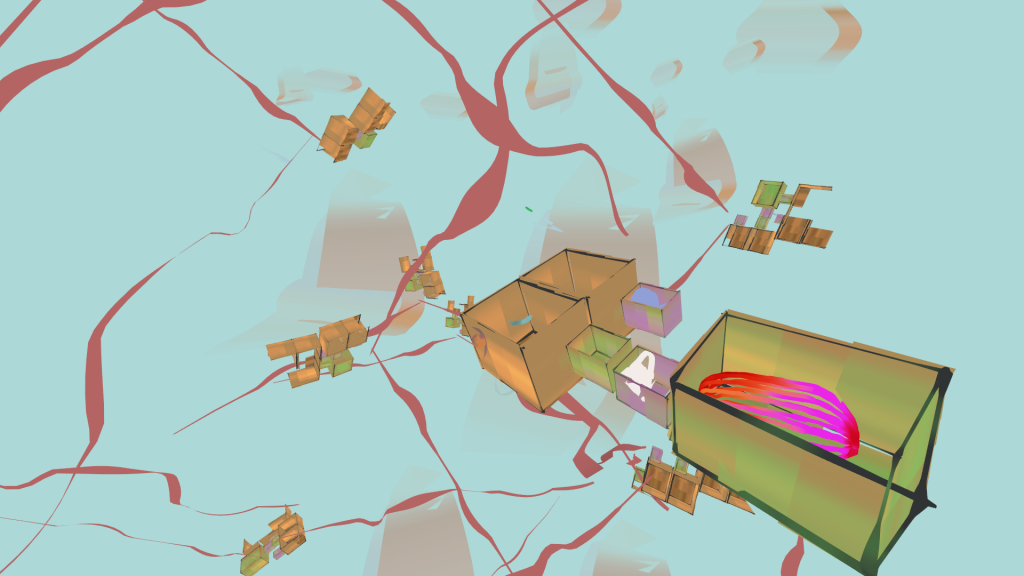

VR + 360

The VR elements within the project were broken down into two parts: 360 film recording using GoPro cameras, and Quill VR, which is an immersive illustration and animation tool used in conjunction with Oculus Rift headsets. Both of these served different functions. The VR filming was used to document and communicate the sites to all of the participants in Rwanda and Kosovo.

Insta_Live

Restrictions in travel and movement across spaces during the COVID pandemic presented the project with a unique challenge – – how could we understand a place from a distance? How could we experience a site whilst being geographically distant? How can we share that experience with peers in different locations? Was it possible to use available digital technologies to facilitate telepresence – ie. the feeling of being there?